The origin of the high temperature of the solar corona, in both the inner bright parts and the more outer parts showing flows toward the solar wind, is not understood well yet. Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, Cambridge, MA, USAĬontext. Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS/Université Paris-Sud, Orsay, FranceĮ-mail: de Paris, Université PSL, Meudon, France Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, CNRS/UPMC, Paris, France Astronomical objects: linking to databases.Including author names using non-Roman alphabets.

Suggested resources for more tips on language editing in the sciences Punctuation and style concerns regarding equations, figures, tables, and footnotes “We’re missing precious information about these solar events… A solar eclipse fills that gap. At Guernsey, we were looking at two types of iron, each of which glows at a temperature of more than a million degrees, as well as helium, which is cooler.

Eclipse sun corona Patch#

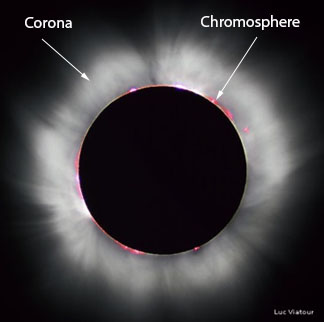

Each ion is created from plasma at different temperatures, so by combining data about several of them, researchers can patch together an idea of the corona’s temperature distribution.

Eclipse sun corona full#

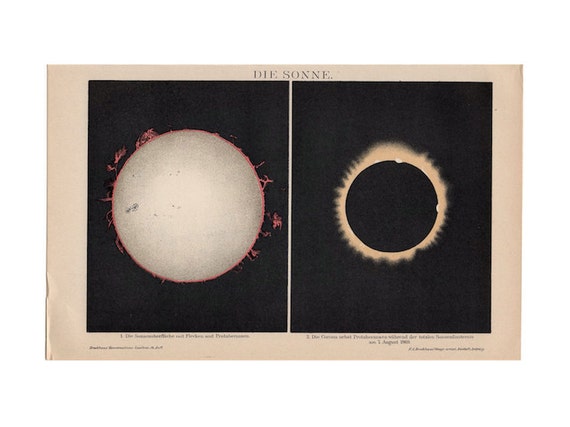

“A solar eclipse fills that gap, and it gives us a chance to make a full map of the corona.”Īlzate and the rest of the Solar Wind Sherpas create their corona temperature maps using sets of telescopes, each with a filter that allows it to view one particular ion in the plasma. “We’re missing precious information about these solar events, about their trajectory and development once they leave the surface,” says Alzate. We can only get data on that ring during a total eclipse. But because the coronagraphs have to block out an area slightly larger than the sun itself in order to prevent too much light from leaking in, there is a ring of space around the sun that neither set of instruments looks at. There are two sets of instruments that study the sun on a day-to-day basis: imagers that look at the disk of the sun, and those that look at the corona by blocking out the disk. Habbal has studied 14 eclipses around the world over 22 years, and her mission, along with the Solar Wind Sherpas, is to create a temperature map of the sun’s corona in order to figure out why it is so hot.Īnd the only time to look at that entire structure is during a complete solar eclipse, when the glare from the sun’s surface stops obscuring the dimmer whorls of the corona. This was one of five groups of Solar Wind Sherpas spread across the western US for the country’s first total solar eclipse in 38 years, headed by Shadia Habbal at the University of Hawaii. A group of researchers and engineers led by Nathalia Alzate from the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy whisked the solar filters off their telescopes to begin taking images of the corona. I was standing in a giant custom tent designed to house the scientific instruments necessary for observing the sun. The obscured sun revealed its corona, a shimmering ring of hot plasma stretching away from its surface like a spiked collar around the new moon.Īs I watched the moment of totality during yesterday’s eclipse, there was an audible gasp and a flurry of activity at Guernsey State Park in Wyoming. A few stars twinkled in the midday sky, and the temperature dropped by what felt like 20 degrees.

The edge of the sun just barely peeked past the moon, the shadow rushed across the landscape towards us at almost 3000 kilometres per hour, and then, abruptly, it was dark. Two minutes of darkness will hopefully shed light on the mysterious ring around the sun

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)